One of Australia's longest-running land claims has been resolved, with land to be handed back to recognised traditional Aboriginal owners on the Cox Peninsula, across the harbour from the Northern Territory capital, Darwin. After a 37-year struggle the federal government is to hand over the deeds to the land in coming months. In 2000, the then Northern Territory Land Commissioner, Justice Peter Gray, handed down a finding singling out six descendants of Tommy Lyons in the land claim, infuriating many claimants who were left out.

A video by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation explains the history. In a time span nearly as long as the 40-year existence of the Land Rights Act itself the Kenbi claim went through numerous court cases, claim hearings and hostility from a succession of Northern Territory governments.

The settlement comprises some 520 square kilometres under “land trust” and 130 square kilometres freehold, which the government considers as “Indigenous development land". The freehold land will be administered through the Larrakia Development Corporation. The settlement package also includes access for all Territorians to what is commonly referred to as the low to high water tide mark, ensuring that they can fish and camp there.

The Kenbi outcome was the main theme of “Land Rights News”, published by the Northern Land Council (NLC), one of four such Aboriginal corporations in the Northern Territory, whose

most important responsibility is to consult traditional landowners and other Aborigines who have an interest in Aboriginal land about land use, land management and access by external tourism, mining and other businesses.

NLC Chairman, Samuel Bush-Blanasi, wrote of “the long struggle for land rights in the Northern Territory, in the face of determined opposition by politicians and bureaucrats”.

“Reading that history leads me to wonder how different the social landscape of the Northern Territory might be if there had been a more enlightened rule over past decades.”

Traditional owner Raelene Singh acknowledged the outcome came too late for many in her family. “It’s brought back memories of them fighting for this land for so long,” she said.

At a press conference about the Kenbi settlement at Parliament House in Darwin on 6 April, the NLC CEO Joe Morrison said “it’s time for reflection, too, as we remember all those who are no longer with us – those who never got to see their rights realised.”

He described the settlement as momentous, adding that the Kenbi land claim had hung over the land like a dark cloud. "Today, that cloud has finally begun to dissipate."

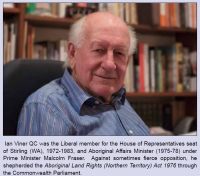

Ian Viner, federal Aboriginal Affairs Minister from 1975 to 78, shepherded the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 through the Commonwealth Parliament against sometimes fierce opposition from politicians, bureaucrats and special interest groups. He writes: “The Land Rights Act is 40 years young. It has a long time to live for generations of Northern Territory Aboriginal people. The Act has proved to be a revolution in the Northern Territory and national relationships with Aboriginal people. In truth it was the foundation for reconciliation which later spread across Australia with the reconciliation movement after the Aboriginal Deaths in Custody Report.” He laments the efforts of many parties since to diminish its integrity.

“When the Aboriginal Land Rights Act (ALRA) was passed in 1976 there was great optimism that the return of ancestral lands to their rightful owners might result in economic improvement, sometimes thought of just in mainstream ways, sometimes in accord with Aboriginal aspirations and wishes,” writes Jon Altman, research professor at Melbourne’s Deakin University.

“If complete Aboriginal control of the key financial institution of land rights was accepted unanimously as a desirable objective in 1984, why is this not the case in 2016, 40 years after the passage of ALRA?”

The claim's 37-year history has divided more than 2,000 Aboriginal people from several family groups who wanted access to the land. Many Larrakia people were unable to legally prove their connection to the land, and left without any major rights to it. About 1,600 Larrakia say they were not recognised as primary traditional owners.

Whereas the NLC hailed the historic settlement some people in the area were angry at being left out of it (video). As many residents in the Kenbi claim area of Belyuen welcomed the prospects of development others were angry they were not recognised as traditional owners, reported ABC News.

CEO Joe Morrison acknowledged that there is ongoing dissatisfaction with the process. “I do acknowledge that the settlement does not have the support of all Larrakia families,” he said. “Their misgivings have focused mainly on the land commissioner’s findings as to who are the traditional owners, and that matter has been a source of great disputation among some of the Larrakia families, even to this day.”

However he says the NLC are unable to do a review at this point in time. “We don’t have statutory power to review traditional Aboriginal ownership with respect to land which is not yet Aboriginal land,” he says.

Others complained of getting “a raw deal”. Ms Roman said: “My dealings with the NLC and LDC have been classical, I mean it's a joke to think anything can be negotiated with them, so I actually see Retta Dixon people as getting a pretty raw deal here."

The big regret about the Kenbi settlement was that “so many of the land owners had not lived to witness history being made,” commented political editor Michael Gordon in The Age and Sydney Morning Herald newspapers.

Other recent Darwin context

As US Marines arrive in Darwin, Australia must consider its strategic position

US Marines welcomed to Top End

Chinese company leases Darwin port for 99 years

US 'stunned' by Port of Darwin sale to Chinese

Minister declines to list Darwin's Aboriginal land as heritage site

Darwin hospital accused of racially profiling singer Gurrumul Yunupingu

Garrmalang festival kicks off

Darwin residents warned about fish possibly toxic from airbase

PM promises $30m for Darwin roads

Wave Hill walk-off protesters march in Darwin

Darwin's iconic mangroves fighting rising sea

Chinese eye off $35m Darwin cold store

Luxury hotel to target high-rollers

Darwin Aboriginal Art Fair Celebrates Ten Years

Crocodiles regularly attacking boats in NT waters