Germany has been looking for a permanent storage site for its nuclear waste for over 30 years. The history of the Gorleben salt dome, a potential nuclear repository, is one full of deception and political maneuvering. And if opponents to the plans have their way, the search might even have to start again from scratch.

The ride down into the Gorleben salt dome takes less than two minutes. When the elevator stops at 840 meters (2,755 feet) below ground, the folding gates open onto a scene that looks like it could be in a modern art museum.

'); document.writeln(''); document.writeln(''); document.writeln('<\/scr'+'ipt>'); document.writeln('<\/div>'); } // --> A sculpture made of old soft drink cans and other scrap metal welcomes visitors as they step out of the elevator. The artwork is meant to symbolize society's unresolved waste disposal problem.

"Trash People" is the name of the work, a creation by the Cologne-based conceptual artist HA Schult. Of the army of similar scrap metal sculptures he installed a few years ago in the site, which is earmarked as a possible permanent repository for radioactive waste, one remains today as a warning, next to an information panel describing Schult's "happening," called "Quiet Days in Gorleben."

The force behind the subversive artworks was Green Party politician Jürgen Trittin, who was German environment minister under former Chancellor Gerhard Schröder's coalition government of the center-left Social Democrats and Green Party. But the art is not the only legacy of the SPD-Green Party era. What is more significant is the research moratorium that the former administration imposed on Gorleben in 2000, putting a stop to research into whether the salt dome was suitable for use as a storage site for nuclear waste.

The drilling machines have been idle since then, and life only returns to the site, which is located in the Wendland region of the northern state of Lower Saxony, when groups of visitors arrive. They are driven through the seemingly endless tunnels in a Mercedes SUV. Anyone who is so inclined can lick the grayish-white salt from the walls. It is apparently of the highest quality.

Bone of Contention

But now the new government plans to allow research activities to resume as soon as possible, and instead of artists and salt dome tourists, the site could soon be buzzing with geologists and nuclear physicists once again. Germany's new coalition government of the center-right Christian Democrats and the business-friendly Free Democrats wants to continue with research into the suitability of Gorleben as a national permanent repository for radioactive waste.

But that isn't likely to happen any time soon, because the SPD, the Greens and the Left Party will not hand over the salt dome to the conservatives without a fight. This month, they plan to petition for the establishment of an investigative committee to look at the Gorleben project. The issue of radioactive waste is set to become a major bone of contention between the government and the opposition.

As the petition states, the purpose of the investigative committee will be to uncover errors and omissions made over a period of three decades "as completely as possible," as well as to investigate "undue exertion of political influence" and "conflicts of interest within the federal government" due to its close ties to industry. Was political manipulation involved in the selection of Gorleben as a site? "The suspicions are very clear," says Sylvia Kotting-Uhl, the Green Party's nuclear policy spokeswoman, who initiated the investigative committee together with other members of her party.

Documents and studies from three decades will now be carefully scrutinized, as will the roles of a number of chancellors, state governors and cabinet ministers.

The commission will be asking a number of important questions. For instance, why did planners decide on Gorleben early on? Why weren't alternatives seriously considered, and why aren't they being considered today? And what happens if the salt dome turns out to be unsuitable?

Back to the Drawing Board

The fact-finding commission will do more than revisit the past. It also has the potential to disqualify Gorleben as a potential storage site once and for all, to take the search for permanent repositories back to the drawing board and put the brakes on the current administration's nuclear policy. The commission will be examining a decades-long history of trickery and deception. It will be confronting the lie that the German nuclear industry is based on, namely the constant postponement and suppression of its waste problem.

Previously unknown documents and interviews with contemporary witnesses already reveal that instead of geology and nuclear physics, partisan politics and power struggles shaped the search for permanent repositories from the start, which is why a feasible solution hasn't been found to this day. But the industry's spent fuel rods will have to be disposed of somewhere. Germany's mountain of radioactive waste, which is growing from one year to the next, cannot be kept in ordinary warehouses forever.

The Germany-based independent expert and research organization GRS, which analyses reactor safety, estimates that German atomic power plants consume about 400 tons of nuclear fuel per year, producing highly toxic waste that remains radioactive for thousands of years. If Germany's nuclear phase-out continues as planned, at least 17,200 tons of spent fuel rods will have to be disposed of, not to mention the irradiated tubes, filters and parts of the reactor vessels of decommissioned nuclear power plants.

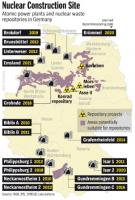

In one of the two above-ground buildings at Gorleben, there are currently 3,500 steel, cast iron and concrete containers of mildly and moderately contaminated waste -- such as cleaning rags, radioactive sludge and moderately radioactive scrap metal -- which are scheduled to be buried in the Konrad repository in Lower Saxony soon. The second storage building contains 91 Castor, TS 28 V and TN85 metal containers of used fuel elements and reprocessing waste. This is highly radioactive waste that officials hope will eventually be permanently stored underground somewhere.

In the coming years, another 43 containers of highly radioactive waste from two reprocessing plants, La Hague in France and Sellafield in Great Britain, will be brought to the Gorleben depot on ships, trucks and trains. Because the transport of Castor containers had repeatedly been met with heated protests, the former SPD-Green Party government in 2002 ordered the nuclear industry to build interim storage sites for used fuel elements next to nuclear power plants, to reduce the need for shipments. As a result of this policy, a portion of Germany's radioactive waste is still being kept in 12 of these interim storage buildings, distributed throughout the country, pending the discovery and development of a permanent repository.

The Welfare of Future Generations

But where should the radioactive waste go? Two former environment ministers are at the center of this dispute, Angela Merkel and Sigmar Gabriel. Both know exactly how polarizing the subject of nuclear energy is. Now Merkel is the chancellor and Gabriel is the chairman of the SPD, and radioactive waste stands a good chance of becoming the focus of their rivalry.

Once again, politics, and not the welfare of future generations, is at the center of the nuclear waste issue. To protect those generations, a site must be found where radioactive waste can be allowed to slowly decay over hundreds of thousands of years, far away from any living creatures. This permanent repository will still have to be impervious in the year 8010, not to mention the year 308,010. Otherwise its contents could poison the living beings of the future if they discovered the contaminated containers, or the waste could gradually seep out and destroy the local environment.

The question, then, is why exactly Gorleben was chosen as the most suitable location to fulfill this role.

Part 2: Politicians Vs. Geologists

The first politicians who clashed over the long-term storage issue in the late 1970s were then Chancellor Helmut Schmidt and Ernst Albrecht, the governor of Lower Saxony at the time. Neither of the two men was particularly well versed in geology or nuclear physics.

At the time, after the first oil crisis, West Germany was developing ambitious plans for nuclear energy. Politicians hoped that by building 50 nuclear power plants, the country could create a source of cheap and inexhaustible electricity. To fulfill this vision, a large permanent repository for radioactive waste was needed. It was also clear what this entailed: a good salt dome, a kind of geological structure deep beneath the earth's surface, which is believed to be particularly stable and impervious to water.

This was bad news for Lower Saxony, which is home to hundreds of salt domes. The federal government's demand to the state's geological research agency was simple: Pick one.

In what resembled a clandestine commando operation, drilling teams arrived in the western Emsland region, near the village of Börger, in early 1976, claiming to be searching for oil. But village residents soon figured out what was going on and quickly formed action groups and drafted resolutions. Local dairy farmers staged protests, fearing that their milk might become tainted by waste from a radioactive storage site and would then be unmarketable.

Eight potential sites were identified, three of them in Lower Saxony. Gorleben was not one of the sites, at least from the perspective of geologists, who believed that sites at Börger, Ahlden and Fassberg were more suitable. But geologists are no politicians.

The Perfect Spot

The governor, Ernst Albrecht, soon decided that he had had enough of the ensuing unrest in his state. Elections were coming up, and Albrecht, who reasoned that the sight of protests at various salt domes in his state would have been his political undoing, wrote a furious letter to Chancellor Schmidt in Bonn. The drilling operations, he wrote, required "significant police protection involving large numbers of personnel." Unfortunately, he continued, this was something he "could not guarantee at adequate levels at the present time."

Albrecht decided to take a pro-active approach to solving the problem and instructed his state geological research agency to search for a suitable site. That was how the name of Gorleben came up. The town was located in a thinly populated area near the border with East Germany. Given the underdeveloped local economy, Albrecht reasoned, the town would surely welcome a major project. In other words, Gorleben was the perfect spot for a long-term radioactive waste storage site -- from a politician's standpoint. But politicians are no geologists.

In their assessment, the geologists pointed out that Gorleben was located in a level 1 earthquake zone -- the only one of the potential sites in such a zone. The experts also noted with some concern that the Gorleben salt dome was beneath the Elbe River. Finally, they wrote that it was highly likely that "there is a natural gas deposit located at a depth of about 3,500 meters below the salt dome," and that any attempts to recover the gas could lead to "large-scale subsidence of the soil." They added that when East Germany drilled for gas across the border, there were "explosions" that destroyed a drilling rig.

Earthquakes, natural gas, explosions? These aren't exactly the words one likes to hear when searching for a permanent repository site designed to last for several hundred thousand years.

Real Dangers

Chancellor Schmidt argued that the Gorleben site was also unsuitable for international political reasons. His government feared that East Germany could even take control of the Gorleben permanent repository in a surprise attack. Bonn ruled that Albrecht's choice could "not be considered."

In politics, there are abstract risks and very real dangers. The fear of earthquakes or an invasion by the East German National People's Army is relatively abstract. But protests at several salt dome sites, on the other hand, represented a very real danger. Albrecht sensed that the fight over a radioactive waste storage site would be "much more contentious" than the controversy over "any nuclear power plant." He clearly outlined the risks in his draft bill: "The nature and size of the potential deployment area, the unpredictable duration of the expected demonstrations and the predictable, extremely determined, methodical and violent actions of nationally coordinated radical groups will require a police operation on an unprecedented scale."

In other words, the less densely populated an area was, the less likely it was that protests would be significant, and the easier it would be to control those protests. Based on these arguments, Gorleben was chosen in February 1977.

The next few years would bring both conflict and benefits to the region. The local hospital argued it needed a new annex, while the fire department said it required 10 new fire trucks, due to the "elevated risk of forest fires." The federal government was happy to pay up, with officials reasoning that a "certain generosity" could only promote local acceptance of the project. Lower Saxony, Gorleben and the neighboring villages received a total of about 500 million German marks (about €256 million), some of it contributed by the nuclear industry.

Thus Gorleben became a pawn in the hands of politicians and business leaders -- a fact that both characterizes and hampers the search for a permanent repository to this day.

Part 3: Sounding the Alarm

Since then, generations of politicians, scientists and civil servants have been embroiled in the debate. For some people, it became a subject they could never forget.

One of them is Helmut Röthemeyer, a professor and physicist. There is probably no one in Germany who has devoted so much of his energy to studying the geology of the Wendland region. Röthemeyer, 71, is now retired and lives at the end of a dead-end street, less than two kilometers from his former office in the northern German city of Braunschweig. He has written a number of books on the subject. He has helpfully laid them out on his dining table, next to stacks of old documents.

Röthemeyer, a tall, gaunt man, walks to the table with a stoop, and he trembles slightly as he flips through the documents -- his life's work. The heading on one page reads "Schedule for 1977," while another reads "Opening in 1990, operations begin in 1994."

The documents reflect the belief held at the time that everything would happen quickly and smoothly. Röthemeyer, a department head at the Braunschweig-based National Metrology Institute of Germany (PTB), was responsible for the Gorleben file. But no matter what the professor and his experts concluded in their analyses, they were constantly confronted with political problems.

It began with Chancellor Helmut Schmidt, whose Chancellery used the initial research results to sound the alarm in 1981. According to a Bonn memo, there was reason to believe "that the salt dome is not ideal from a geological standpoint." The experts took the hint. But Schmidt's SPD-FDP coalition government, anxious not to jeopardize the project's support within the Lower Saxony state government, did not take the necessary action.

A Precautionary Measure

Two years later, in the spring of 1983, Röthemeyer and the PTB institute submitted another interim report. By this time, geologists had examined the layers of rock above the salt dome and concluded that it was possible that they were not impermeable. "In light of the unknowns surrounding Gorleben, I wanted to suggest in the report that investigations be conducted at other sites as a precautionary measure," Röthemeyer recalls today.

But that was unacceptable. Once again, there was trouble with Bonn, this time because the experts' proposal was not what the new conservative administration of then-Chancellor Helmut Kohl wanted to hear. The new chancellor's staff sent Röthemeyer a telex, in which they wrote: "The question about other sites should be removed from the document." Determined not to allow a search for alternative storage sites to trigger nationwide unrest at any cost, they decided to focus their efforts on the struggle over Gorleben. It was a battle they waged using every tool in the state's arsenal against the anti-nuclear activists who were protesting there-- including water cannon and police cordons.

It was only Kohl's successor, Chancellor Gerhard Schröder, a Social Democrat, who put an end to the controversy when his administration abandoned the investigation in Gorleben in 2000, as part of a deal reached between the SPD/Green Party coalition government and energy companies to phase out nuclear power. The government argued that it was essential to clarify what was going to happen with the country's radioactive waste, and that alternative sites should also be considered.

Röthemeyer's opinion was no longer in demand. "In the past, we Germans were highly sought-after at international conferences, because Gorleben put us at the forefront of the global radioactive waste storage issue," he says. According to Röthemeyer, no country was as far along in its research on long-term radioactive storage as Germany was. But the government's decision to suspend the research changed everything. The Swiss and the Finns are now setting the tone, and experts at international conferences have little to say to Röthemeyer these days.

Tighter Rules

In Germany's last national election campaign, nuclear energy was one of the few polarizing issues. Then-Environment Minister Sigmar Gabriel had placed the storage site issue on the agenda, accusing the members of the former Kohl administration of manipulation and insinuating that Chancellor Merkel may have also played a role. "I think Ms. Merkel has good reasons to distance herself from her predecessor," Gabriel said, to raucous applause from his supporters. He was elected chairman of the SPD soon afterwards.

As environment minister, Gabriel drastically tightened the requirements for the planned German radioactive waste storage site. The new rules require, for example, that "no more than very small amounts of hazardous materials can be released from the permanent repository" for more than 1 million years -- a substantial increase over the previous figure of 10,000 years.

According to another of the new requirements, "the recovery of waste from the permanent repository" must be possible in an emergency, and over the long term. The underground technology must remain accessible and modifiable for future generations. In contrast, the intent of the previous set of standards was to bury the radioactive waste in the salt dome in such a way that it would be irretrievable and ultimately inaccessible.

Given these requirements, a search for alternative sites is in fact inevitable. And politically speaking, at least from the standpoint of the SPD, it is highly desirable, because such a search can only harm the Christian Democrats. If scientists began looking for alternative storage sites in other parts of Germany today, it would trigger as much unrest as the supposed oil exploration teams did in Lower Saxony in the 1970s.

Not in My Back Yard

Gabriel knows from experience how burdensome the waste issue can become. The controversies over the annual Castor transports were already a thorn in his side when he was governor of Lower Saxony. "Those who think nuclear energy is so wonderful should take on its waste," he once told a group of CDU state governors.

Gabriel cleverly put forward regions that were earthquake-proof and where clay deposits offered impermeability to water -- regions that, as he argued, might be more suitable than the salt dome in Lower Saxony. It just so happened that these more desirable geological formations were particularly prevalent in the southern states of Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg, states which were governed by the CDU and its Bavarian sister party, the CSU.

Not surprisingly, many conservatives were horrified when, under the CDU-SPD grand coalition government which was in power from 2005 to 2009, the Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources (BGR) published a study on possible permanent repository sites in Germany. In Baden-Württemberg alone, the institute identified two regions as being "worth investigating."

One of those regions is Donautal near Ulm in the southwestern state of Baden-Württemberg. Although studies have only identified the region's Opalinus clay deposits as potentially suitable as a permanent repository site, local resistance soon developed, with activists quickly finding counter-arguments against the BGR's analysis. "Baden-Württemberg is one of the most seismically active regions in Germany," says one of the movement's leaders, Karl-Ernst Lotz. "The last quakes were quite noticeable."

Federal Research Minister Annette Schavan (CDU), whose electoral district could possibly be the location of a future Donautal repository, has also weighed in. "A suitable site has already been found," she says. "So far, no one has been able to plausibly demonstrate that the Gorleben salt dome is not suitable."

Part 4: Bowing to Pressure from the South

Another potential permanent repository site, near the Swiss border, would be adjacent to the election district of the Christian Democrats' floor leader, Volker Kauder. He, too, is keen to sing Gorleben's praises. "A suitable permanent repository site has already been found in Lower Saxony, and that project should finally be realized," he says. The state Environment Ministry in Stuttgart, for its part, was quick to issue a statement pointing out that the Opalinus clay formation in the whole of Baden-Württemberg is "unsuitable."

And then there is Bavaria, which could also offer alternatives, such as sites in the Fichtelgebirge mountain range or in the Bavarian Forest, with its solid granitic layers. "There is not a single site in Bavaria that is as well suited as Gorleben," claims Markus Söder (CSU), the state's environment minister. "That has been the conclusion of every study."

Nine of Germany's 17 nuclear power plants currently in operation are located in Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg, and the governors in Munich and Stuttgart have traditionally supported nuclear power. Why, then, are these two states refusing to take responsibility for the radioactive waste produced there? "It's not a question of federalism, but of geology," says Kauder, who isn't exactly known as a geological expert.

The Chancellery in Berlin has also bowed to pressure from Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg, despite its initial willingness to look into other possible repository sites. "Merkel's then-chief of staff, Thomas de Maizière, had initially indicated that the chancellor also supported a search for alternative sites," says Gabriel, recalling his tenure in the grand coalition. But then, he adds, the southern state governors balked.

Their position on radioactive waste reflects the view held by most Germans. According to a 2002 survey by the Institute for Technology Assessment and Systems Analysis (ITAS), 73 percent of Germans felt that a permanent repository for radioactive waste was urgently needed, but only 19 percent said they would tolerate one in their state.

These attitudes are reflected in the fierce reactions of those most affected by the issue: the residents of the Wendland region around Gorleben. After a number of relatively quiet years, protests have become more strident since the last election.

A Blast from the Past

At about 10 p.m. on a Saturday evening last fall, for example, five tractors, honking their horns, suddenly emerged from a forest and proceeded toward the gate marking the beginning of a restricted area surrounding the Gorleben site. The first of the tractors came to a stop only a few centimeters in front of a police officer. Suddenly 100 activists were facing off against a handful of nervous police officers, while the Italian partisan song "Bella Ciao" blared from speakers on one of the tractors. The protestors were carrying signs that read: "Block. Sabotage. Destroy." It was a scene reminiscent of the heated anti-nuclear protests of the 1980s and 1990s.

In the dark, masked figures stealthily walked up to the security fence, cut the wire mesh and stormed the site. Within a few minutes, bonfires were burning on the grounds, casting a blood-red glow on the drilling tower, which contains an elevator that is supposed to eventually transport radioactive waste into the depths of the storage site. The activists calmly took control of the premises, spraying the walls with graffiti. Police reinforcements did not arrive for another hour, when they pursued the protestors and arrested some of them.

It appears that the days of sit-ins and water cannons are about to return. Environment Minister Norbert Röttgen (CDU) has until March to submit a bill on the planned permanent repository to the cabinet, a deadline that will mark the end of a 10-year research moratorium. There is no doubt that the government will reopen the salt dome and allow the research activities to resume. "We have to concentrate on Gorleben now," says Röttgen.

But even without the investigative committee, the nuclear industry is not in a position to simply pick up its work at the Gorleben salt dome where it left off. First it will have to hire and train new employees, revise its plans and dust off its drilling machinery. According to a "Plan for the Resumption of the Gorleben Permanent Repository Project" developed by the Federal Office for Radiation Protection (BfS), the work could not resume before 2013 -- and even then only if the federal government approves an annual budget of between €150 million and 200 million ($217-290 million). In other words, as the plan states, the entire endeavor will be extremely "costly and time-consuming."

And then, say the BfS officials, a certain legal problem will be a "top priority." What about the legal rights of use for the salt dome? Put differently, whose permission does the government require in order to dig additional tunnels underground?

The problem stems from the fact that the land above the salt dome is privately owned, by farmers, aristocratic landowners and church parishes. Some of the 125 owners have always opposed the project, while others awarded the federal government only limited rights of use in the 1980s. These agreements expire in 2015 -- at which point the owners can simply tell the government to get lost.

An Obligation to Future Generations

Andreas Graf von Bernstorff is driving his Land Rover along a sandy path near the research site, through a pine-and-birch forest. "I own the forest," he says.

Many years ago, the auto industry wanted to buy his forest and install a waste storage site on the land. It was a very attractive offer: 27 million German marks for 670 hectares of sandy, wooded property, 10 times as much as the forested land was worth. But Bernstorff decided not to sell.

Bernstorff is an affable, absentminded country gentleman with a penchant for hats and cigars. "I tend to be conservative," he says. He was a member of the CDU when the debate over nuclear power erupted for the first time. On the other hand, as a member of the aristocratic Bernstorff family, Bernstorff, who holds the title of count, also had obligations. A family rule stipulates that he is required to pass on his lands to future generations in as pristine a condition as possible. In short, he feels obligated to both his ancestors and his descendants. Bernstorff has tried to convince local farmers to take his side, but, as he says, not all could resist the "temptations" of the nuclear industry.

Environmentalists and hippies came to his forest and built an "anti-nuclear village" to protest nuclear energy. "We tried everything," says the stubborn count, "and at some point we even had an Indian here who cursed the place." He is referring to Chief Archie Fire Lame Deer, a Lakota medicine man. Bernstorff climbs down from his Land Rover and runs his hand across a weathered totem pole. Every other Sunday, to this day, anti-nuclear activists meet at the site and pray.

But it isn't just this spiritual resistance that the federal government will have to overcome. Before proceeding with any further investigations on the site, it will have to make a deal with Bernstorff, or at least with the farmers in his vicinity, and that will be expensive. "The price has to be right," says Klaus Wohler, a member of an organization called the Interest Group of the Owners of Salt Rights.

Legal Setbacks

In addition to the property owners, the government will have to contend with residents from the surrounding communities. Up until now, the federal government and the industry has carried out its research at the salt dome behind closed doors. But it now appears that planning permission hearings, in which citizens would be involved, may be required in Gorleben in the future. The process could lead to tens of thousands of objections and a public hearing, which could turn into an anti-government forum reminiscent of the large-scale protests against the construction of a nuclear waste reprocessing plant in the Bavarian town of Wackersdorf in the 1980s.

If planning permission is ever granted for Gorleben, a wave of lawsuits seems inevitable. In the absence of an objective comparison of different sites and scientific criteria for the selection process, no decision to build a permanent repository at Gorleben would stand up in court. The chancellor, on the other hand, believes that "an exploration of alternative sites is unnecessary at this time." That doesn't sound like a very scientific approach.

But what happens if scientists determine, in five or 10 years' time, that the Gorleben salt dome is not suitable, or if the popular protests become too loud? How confident can the government be that a project that was approved in 1980, under the conditions that applied at the time, will still hold up in court in 2025? If it doesn't, Germany, after decades of research work and billions of euros in investments, will have to start all over again.

Even within the Christian Democrats, there are cabinet ministers who expect that to be the outcome. "If you ask me, our highly radioactive nuclear waste will not end up in Gorleben one day," says one minister, who preferred not to be named, "but in a Russian repository built according to Western standards."