Guardian Australia exclusive: Doctor responsible for mental health of people in detention becomes the most senior figure to condemn system from within, saying immigration department deliberately harms vulnerable detainees in a process akin to torture

The chief psychiatrist responsible for the care of asylum seekers in detention for the past three years has accused the immigration department of deliberately inflicting harm on vulnerable people, harm that cannot be remedied by medical care.

“We have here an environment that is inherently toxic,” Dr Peter Young told Guardian Australia. “It has characteristics which over time reliably cause harm to people’s mental health. We have very clear evidence that that’s the case.”

Young is the most senior figure ever to condemn the detention system from within. Until a month ago he was director of mental health for International Health and Medical Services (IHMS), the private contractor that provides medical care to detention centres on the Australian mainland, Christmas Island, Nauru and Manus Island.

Young has extensively briefed Guardian Australia about a system he says is deliberately harsh, breaks people’s health, costs a fortune, compromises the ethics of doctors and is intended to place asylum seekers under “strong coercive pressure” to abandon plans to live in Australia. “Suffering is the way that is achieved.”

Young strongly criticised the immigration department for:

• Delays that endanger health in bringing patients to Australia from Manus and Nauru: “It is seen as undesirable because it undermines the idea that people are never going to Australia and also because of the concern that if people arrive onshore then they may have access to legal counsel and other assistance.”

• Leaving people in detention who are acutely suicidal: “Trying to manage them in a non-therapeutic setting like that is just inherently futile. It’s not going to work.”

• Returning patients with less severe problems to detention despite medical advice that they cannot be expected “to fully respond to treatment in an environment that was making them sick”.

• Misusing patient information. “People disclose a lot of personal information which is then recorded in notes which are then available to non-medical people for other purposes.” Young says the dual role of IHMS staff treating detainees but reporting to the department raises fundamental ethical problems for doctors in the system.

• Displaying an obsession with secrecy: “Speaking out of turn is clamped down on whenever it occurs … they continue to maintain the fantasy that they can keep everything a secret.”

• Reluctance to gather and use mental health statistics that might “result in controversy or threaten the application of the policies of deterrence”.

• Directing doctors not to put in writing that detention has led to deterioration in their patients’ mental health. IHMS doctors ignored the direction. Young said they saw evidence all around them of detainees “sick because they are there and getting sicker while they remain there”.

Guardian Australia contacted IHMS and the immigration minister for comment, neither responded.

The Manus camp particularly appalled Young. “When you go to Manus Island and you walk down what is called the ‘walk of shame’ between the compounds and you see the men there at the fences it’s an awful experience,” he says.

“You have to feel shame. You have to understand what that feeling is about in order to be able to be compassionate. By feeling the shame you stay on the right side of the line.”

Young told Guardian Australia IHMS figures had shown for some time that a third of adults and children in the detention system had what he called “a significant-level disorder”. If they were living in Australia, that would require the care of specialist medical health services. The figures only got worse as detainees stayed longer in detention: “After a year it approaches 50%.”

Last week, in alarming evidence to an Australian Human Rights Commission inquiry, Young said the immigration department had refused to accept IHMS statistics proving damage to children and adolescents held in prolonged detention. He told the inquiry: “The department reacted with alarm and asked us to withdraw the figures.”

In a belligerent appearance before the inquiry, the secretary of the immigration department, Martin Bowles, accused the president of the Human Rights Commission, Gillian Triggs, of making “highly emotive claims” about health problems in the detention system. He had not heard evidence of the problems provided by Young and other IHMS doctors earlier in the day.

His hand shook as he confronted Triggs. When his evidence produced laughter he demanded the room be silenced. He refused to answer some questions and retreated at times behind a wall of bureaucratic prose.

But Bowles did not deny a link between prolonged detention and mental illness. He called this a “well-established” issue and insisted his department was doing “everything it humanly can” to provide “appropriate medical care” to address the mental health problems of detainees.

Young told Guardian Australia that was impossible: “The problem is the system.”

Young is confident that in his time at IMHS the men and women working for him made better assessments of detainees’ health and delivered much better treatment than in the past.

“But you can’t mitigate the harm, because the system is designed to create a negative mental state. It’s designed to produce suffering. If you suffer, then it’s punishment. If you suffer, you’re more likely to agree to go back to where you came from. By reducing the suffering you’re reducing the functioning of the system and the system doesn’t want you to do that.

“Everybody knows that the harm is being caused and the system carries on. Everybody accepts that this is the policy and the policy cannot change. And everybody accepts that the only thing you can do is work within the parameters of the policy.”

The window of reasonableness closesYoung arrived in the system in 2011 at a crucial moment: the high court was about to knock back the Gillard government’s proposed “Malaysia solution” and, as the boats arrived in ever-increasing numbers, the detention system was bursting at the seams. So the government began processing detainees quickly and releasing large numbers into the community on bridging visas. “The problems that we were seeing from a mental health perspective decreased massively.”

Young has been a psychiatrist for nearly 20 years, most of that time working in public health. He joined IHMS believing the detention system was problematic but confident that good could be done from the inside. “I felt that given the experience I had I could work between the immigration department and IHMS and the detention health advisory group to bring about positive change.”

The year before Young’s arrival, the immigration department had been put on notice once again that prolonged detention harms mental health. Professor Kathy Eager of Wollongong University reached that conclusion in a study commissioned by the department itself.

“There is,” she wrote, “almost universal criticism of the policy of detaining asylum seekers, particularly in terms of the mental health implications.”

Her findings were backed by the department’s independent Detention Health Advisory Group (Dehag), the Australian College of Mental Health Nurses and the Australian Psychological Society. In 2011 the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists declared: “Prolonged detention, particularly in isolated locations, with poor access to health and social services and uncertainty of asylum seeker claims, can have severe and detrimental effects.”

While detainees were being rapidly released, Young observed attitudes towards them improved throughout the system. They were not treated as prisoners.

Their mental health was generally good: “These people are actually quite robust and psychologically healthy individuals despite all the suffering that they have been through.”

But what Young calls “the window of reasonableness” stayed open for only six months. With boats arriving in unprecedented numbers and the opposition in full cry, the government reversed direction. Once again boat people were to be held for long periods. The camps on Manus and Nauru were reopened. Kevin Rudd announced that no new boat arrivals would end up living in Australia.

“You just can’t overstate how things changed so rapidly when the policy changed,” Young says. Once again the system treated them as prisoners. The impact on their mental health was as predicted: fine for a few months, then increased depression, anxiety and stress.

“Most people have a level of resilience which allows them to function fairly well for a few months, but after that time there is a steady deterioration … after six months the cumulative harms accelerate very rapidly.”

Uncertainty does the worst damage, Young says. Then comes hopelessness. “They are constantly given a message that they are on a negative pathway, meaning their claim is not going to be accepted. This is despite what we know about the outcomes of processing in the long term, which is that greater than 80% of people are found to be genuine refugees.”

And they have so little autonomy. “Just the day-to-day daily lives that they experience living in the detention system means that they have very little control over what they do. It makes things particularly difficult for people who are there with their children as well. Their capacity to act as parents and to make decisions on behalf of their families is so restricted.”

Young sees immigration detention as inherently more harmful than prison. “In prison those with mental health problems generally improve. People are more well on their release than when they entered. What we see in detention is the opposite of that. Over the course of time in detention, they get sicker.

“We don’t have families in prisons. Secondly, when people go to prison they go through a recognised independent judicial process. It’s not arbitrary. This is an arbitrary process and people see it as being unfair and that is another factor.

“Also, when people are in prison they have a definitive sentence so they know there is an end point. This is not like that at all. This is indefinite.”

Each quarter IHMS presents the department with figures on the health of detainees. The data for July to September 2013 showed a third of those held in detention for more than a year were experiencing extremely severe depression; 42% were suffering extremely severe anxiety; and 42% were extremely stressed. The report notes these figures are consistent with internationally published research: “The pattern shows the negative mental health effects of immigration detention with a clear deterioration of mental health indices over time in detention.”

Abbott takes power“People didn’t really take Rudd seriously,” Young recalls. “But everybody was saying when the Libs get in it’s really going to get tough. So there was a building up of expectation that things were going to get worse, which made it worse in itself.”

When the change came in late 2013, there was no radical shift in policy. “Everything just got harsher.”

Relations between the department and its independent health advisers were already rocky. Dehag had been set up in 2006 at a time of acute embarrassment after it was discovered that a schizophrenic Australian resident, Cornelia Rau, was being held in the detention.

She was thought to be German, was desperately ill and the immigration department refused to release her for treatment. She was finally identified naked in the yards of the Baxter detention centre.

Dehag had an independence the department came to regret. Its dozen members were nominated by peak medical authorities, including the Australian Medical Association, the Mental Health Council of Australia and the professional colleges for nursing, general practitioners and psychiatry. The experts were at the table but the department found itself dealing with people who could neither be corralled nor muzzled.

“It’s always been a very tense relationship,” says Louise Newman, director of the centre for developmental psychiatry and psychology at Monash University. Newman chaired the group for a time. “At every meeting until they disbanded us we would make a statement that we did not support mandatory detention or prolonged detention of any form, that it was damaging and that it created problems that we could not fix.”

Young, who sat in on the group’s meetings, confirmed the experts’ fundamental objection to detention: “That’s been the baseline position that they have always held and they have always presented.”

The group watched with concern as the Gillard government reversed its policy of swift release for asylum seekers. Newman sees the second round of detention as worse than the first because it came as the evidence of harm was even more firmly established. “They replicated the very conditions that they have admitted contribute to mental harm and deterioration,” she said.

“It’s seen as collateral damage. The department does what it can to reduce it but in the name of the greater good of border protection and deterrents it doesn’t really matter. We’re saving lives by sending people mad.”

The group drove change. “The department was very pleased to use things that we brought in, so any positive reforms that have gone on in the system in terms of screening people and healthcare and health standards were all done by Dehag.”

But Newman alleges the department later sabotaged medical screening of asylum seekers for signs of torture and trauma. “We argued that no one who had been tortured should be detained or particularly not in remote places. The departmental doctors decided the best way to get around that was not to do the screening, so they didn’t find out who was tortured. They stopped it on Christmas Island so people could be shipped away before it was even known if they were trauma survivors.”

Tension between Dehag and the department intensified after Bowles was appointed secretary of the department in 2012, Newman says. Bowles is not a doctor but for much of his career was a health administrator before joining the defence department. He is one of a group of former army and defence figures who now hold the most senior positions in the immigration department.

Bowles announced a review of Dehag, which he renamed the Immigration Health Advisory Group (Ihag). He failed in manoeuvres to change its membership but imposed a former military doctor, Paul Alexander, as its chairman. “It was meant to be a much more controlled group,” Newman says.

Bowles wanted the experts to withdraw from public debate. Young says: “They wanted the thing to be more watertight.” The experts were not accused of leaking. “But they expressed views in public which were relevant to the business before the committee.” They continued to do so. The most vocal was Newman.

The experts and the department continued to be at loggerheads over the standard of care for detainees. Newman says Dehag and Ihag always argued that detainees had to be looked after “regardless of visa status” while they were in Australian hands, and it was an ethical obligation on all medical practitioners working in the system to provide care to Australian standards.

But once Nauru and Manus reopened, the department began to demand treatment be pegged to the much lower standards of care on those islands. There would have to be exceptions – no inpatient mental healthcare is available on Manus or Nauru – but the department’s wish was to lower the general standard of care for detainees in those camps.

At what was to be the last meeting of Ihag in August 2013, the issue was debated at length. An impasse was reached, says Newman. “The department at a very high level from secretary down argues the Australian government is not obliged to provide our standard of care to these people.”

But experts insisted that standards must be maintained and that the department’s plan was an ethical minefield for doctors. “Clinicians who go along with it are absolutely compromised,” says Newman.

Ihag experts continued to work in the system, but they never met as a group after Abbott’s victory in the federal election of September 2013. A long pattern of suddenly cancelled meetings ended with no meetings called at all. In mid-December the experts received letters thanking them for their service. They were dismissed. Alexander was now to be the sole adviser on medical matters to the renamed Department of Immigration and Border Protection.

Scott Morrison, the new minister, issued a statement: “The large membership of the group made it increasingly challenging to provide balanced, consistent and timely advice in a fast-moving policy and operational environment.”

Young says: “That doesn’t wash at all. Ihag had consistently told the department things it didn’t want to hear and the department had pretty transparently sabotaged the operation of it for more than 12 months.”

The chiefs of peak medical bodies, including the AMA’s Dr Steve Hambleton, expressed shock at Ihag’s demise. Abbott condemned the generally negative reporting of the move as “a complete beatup by the ABC and some of the Fairfax papers”. The prime minister declared: “This was a committee which was not very effectual.”

The rising tide of dataMorrison had been in the job only a few months when he assured Australia that mental health problems among detainees were on the wane. In mid-December, Nine News reported: “Immigration minister Scott Morrison yesterday said diagnosed mental health problems among detainees in Australia had fallen from a peak of 12% in 2011 to the current rate of 3.4% as a result of greater resourcing.”

Young is scathing about Morrison’s figures. “That’s not a prevalence rate. It never has been. It’s a pale shadow of what the real prevalence rate is because of the way that data is derived.”

Young says Morrison was ignoring the figures revealed by regular screening and instead using a count of visits to GPs or psychiatrists where mental health problems were raised. “It doesn’t take into account people who may have a disorder who are not seeing either of those two categories of clinicians.”

Gathering better statistics was one of Young’s key ambitions in his time at IHMS. The department dragged its feet on his proposals to use new measures to screen mental health problems. “There seemed to be a fear that it would result in controversy or threaten the application of the policies of deterrence,” Young says.

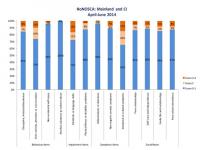

But the chief psychiatrist finally got his way and the new measures were used for the first time in the first quarter of this year. Young presented these figures to the Royal College of Australian and New Zealand Psychiatrists in May. They confirmed the long-established pattern: about a third of all those in detention had clinically significant problems – and the longer the detention, the worse the problems.

Half those who had been detained for 19 months or more were extremely or severely depressed; 40% were extremely or severely stressed; and 40% were extremely or severely anxious. The worst scores were gathered on Manus and Nauru. But the figures show a common pattern across the whole detention system.

In a PowerPoint presentation provided to Guardian Australia by the college, Young concludes: “All show linear deterioration in mental health status over time in detention.”

Young’s staff were also collecting figures on the impact of detention on children. “Changing to instruments more appropriate for children has been something the department has dragged their feet on for quite a long time.”

Young shocked the Human Rights Commission inquiry last week by alleging the department refused to accept these Honosca (Health of the Nation Outcome Scales for Children and Adolescents) figures.

He told Guardian Australia: “This is not the only instance where data which has been seen as controversial or just difficult to understand has been buried.”

But Triggs requested the figures be given to her inquiry. They show across the mainland detention system a large number of children showing emotional distress or related symptoms. Young considered the figures a sign of serious problems that needed urgent consideration and action. Some of these children are those that IHMS doctors reported as showing issues of self-harm, regression, aggression, bed-wetting and despair.

When Bowles was questioned at the inquiry, he did not deny his department issued instructions to IHMS to withdraw the figures but was at pains to suggest to the commission that they remained under consideration by the department. He said: “I have no doubt that most of this sort of reporting is mainstream.”

Giving evidence to Triggs’s inquiry was Young’s last assignment for IHMS. As his three years with the commercial providers drew to a close, he decided to make a professional and public assessment of the detention system once he was free to do so.

“As a medical practitioner your duty is always to your patients and the people you look after,” he says. “To them you have a broader moral and ethical responsibility. In this case you see harm being done and as the primary duty of a doctor is to do no harm, your duty is to speak out against that harm – to say that harm should not be done.”